"Investing is at its most intelligent, when it is at its most business-like" -- Benjamin Graham

Thursday, September 28, 2006

An offer from the Strategic Investor

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

DCF for TRLG

Unfortunately there was a problem with Blogger photos, so it didn't embed.

So, I will try again.

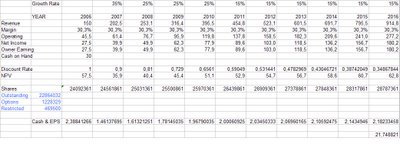

The model covers a ten year valuation of the company. Basically, what I have done is take the actual net cash and equivalents as of December 31, 2005, and the actual number of shares outstanding, plus the number of options outstanding, plus the number of restricted stock shares issued, and project the following: annual revenue growth, operating margins, tax rate, net income and owner earnings (net income plus depreciation less capital expenditures), and future equity dilution.

Starting with 2006, I project revenues of $150 million. This represents a 50% increase over last year's $102 million, and is roughly the amount that management projects. Going forward, I expect slower growth. It is possible that my growth rates are too conservative, but how mainstream can $300 jeans be? International sales are also flagging, though management has insisted that this will improve shortly. Management insists that it can turn the brand into a $1 billion per year business, though how long is not clear.

Next up is margins - a measure of how profitable those revenues are. The company appears to be consistently running an operating margin of 30.3%. It is important to distinguish between gross margins and operating margins. Gross margins is the spread between the sale price and the cost of the product sold, expressed as a percentage of the sale price. Thus, if sell for $300 a pair of jeans that cost you $150 to produce or purchase, your gross margin is 50%. However, there are still the other operating expenses, like employee, marketing, legal, and others, to pay. These are generally lumped together under Selling, General and Administrative expense. After you pay those expenses you arive at operating margins. That is, your profit as a percentage of sales after you have paid all operating expenses.

(Please note that the spreadsheet is in a German version of MS Excel, so don't be thrown by the commas. Germans use commas where US uses decimal points, and vice versa. Funny, isn't it? But I digress).

TRLG has benefitted from higher margins in recent months, expanding to about 52-53%. Most of this margin expansion is coming from the impact of retail stores, which enables the company to capture the additional gross profit between wholesale and retail. Unfortunately, it also means the company has proportionately higher selling, general and administrative expense, because there are rent, employees, utilities and other expenses to pay in operating that retail store, so operating margins are remaing about the same as before the retail stores. (The amount of revenue is higher, because revenue is now happening at retail, and not only at wholesale prices, so that margin is being earned on a higher top line number).

From there one has to consider interest expense (none, since the company has no debt, and appears to require no major investment to grow revenues, since all products are produced by contract manufacturers). This leads us to taxes. I assume a tax rate of 35% for all years. Here, I am simply projecting the current maximum corporate tax rate into the future. This is actually one area where I have not been conservative. It is likely that the US government will raise taxes, particularly on corporations, in the next 10 years, in order to combat rising deficits.

After the taxes are paid, we have Net Income. To this we need to add depreciation (a non-cash expense), and subtract capital expeditures. In mature businesses, these numbers are often very similar, as the business tends to need relatively little capital. What makes TRLG interesting is that it has virtually no cap-ex at all. In fact, it has virtually no long term capital commitments, other than some leasehold improvements at its corporate offices and retail stores.

So, Net Income and Owner Earnings are essentially the same.

The Discount Rate

One of the most crucial numbers you can chose in investing is an appropriate discount rate. The discount rate is used to reflect the time-value of money. Obviously, if I offered you $1 today or $1 in ten years, you would rather have the $1 today. I have to "discount" the value of the dollar in ten years to reflect the risks that you assume in waiting so long to get your money.

The first time they hear this, most people think of inflation, and in fact the idea is very similar. But where inflation measures the discount that would be required to maintain purchasing power, investors need to use a different number. We have to ask ourselves, what is the opportunity cost of the capital? Since if we didn't put our capital into this investment we could put it into a different one, we should really use a number that reflects what would happen if we were to earn the market return. I estimate this at about 10% (though in my first post I mentioned that the compounded rate of return of US stocks since 1926 is actually 9% - and that was in 1999 at the height of the bubble).

Once I have discounted those earnings into the future, I then need to divide the discounted earnings by the anticipated number of shares outstanding, so see how much earning power one share should have.

Thus far this year, management has cut out issuing itself options. Instead, it issues itself restricted stock. This year, the company issued employees 450,000 shares of restricted stock (it also issued some as settlement to outsiders). I see no reason to expect that management will become more frugal going forward, so I estimate the increase in shares outstanding by 469,000 per year. I then divide each year's discounted earnings by the anticipated shares outstanding.

All that is left to do is sum up the values. This produces a Net Present Value (reflecting the sum of all the present values) of the future cash flows of the company. Those cash flows are worth about $22.

Unlike most DCF models, I am assuming no residual value beyond the measurement period (generally, investments in stocks are considered to have infinite valuation periods, and you have to do that special calculation. In the case of this stock, where the true long term sustainability of the business is really a question it makes no sense to assume an infinite valuation period. The extra margin of safety is key).

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

I've left the temple of True Relgion

On Thursday, I unloaded my entire position in TRLG at $22.60. The stock hit an eight month high, near its all time high of $24.61, and this time I became concerned about valuation, and decided to take my 66.7% gain and run. The stock may head higher, but I believe that it will go lower again; indeed, it closed at $21.45 yesterday.

It should be noted, however, that evaluating an investment is an art, and not a science. While the math is straightforward, you have to make many estimates, because there are many possible outcomes. Buffett speaks of the need to have a range of values for a stock (and then watch developments and re-handicap the possible outcomes as events unfold). The quality of these estimates and the ability to estimate the probability of one of the outcomes over the other are the keys to success. So let’s break down my rationale for believing that the above estimate is approximately correct.

Reason 1: Valuation

The primary reason I sold was that my numbers told me to. I ran the numbers and concluded that the fair value of the stock is about $21-$22, so I sold at a slight premium to that value. As you can see from the embedded Discounted Cash Flow analysis, I estimate pretty strong revenue growth going forward, with ten years of growth above 15%. At the moment, the company is growing 50% over the prior year, but this is already a slower growth rate than 2005 was over 2004 (you can only compare the fourth quarter). As the revenue base continues to grow, I expect that in percentage terms revenue growth will continue to slow.

Revenue growth is the key to this company’s share price. The company’s price has almost nothing to do with the assets on its books. The price is entirely dependent on the expectation of future earnings growth. Thus, if earnings falter, even a little bit, the stock price is going to be hurt. Of course, that happens for all companies, but companies that have a market cap closer to their book values have a natural buoy to their share price – the fact that the assets on their books have value, and could be sold.

As of the second quarter, TRLG has $57 million in assets, against $7 million in liabilities. This is enough to get any investor’s attention. Better yet, $50 million of that is in current assets. The company has far more money in cash and short term investments than it has in liabilities. In short, the creditworthiness of the company is tremendous. In fact, almost none of its assets are actually used in the business. The company has about $20 million in working capital, and $2 million in property plant and equipment, substantially all of which is leasehold improvements at its corporate offices, warehouse and retail locations. In fact, the company appears to require no long term assets to run its business. This is a wonderful thing, in my mind, because its return on capital employed (ROCE), the capital actually used to run the business, is about 125%. These are the kind of numbers that had me buying at $13.50. But at that time, I estimated that the stock was conservatively worth $20 per share. While intrinsic value has grown somewhat (to almost $22), the market has come to value the company at that level, too. I don’t want to speculate on the market now overvaluing the company substantially, as betting on the market’s irrationality also requires me to bet on which direction that irrationality will take. Since by its nature the behavior would be irrational, it’s a fifty-fifty bet. I look for better odds.

The problem is, with $50 million in net assets, the company trades at over $500 million – for a price to tangible book of 10 times. The market is offering this company a tremendous amount of goodwill, because it is very well managed, but if there is even a small slowdown, Jim Cramer will be shouting “CLEAR!” as the price drops painfully. Since even well managed companies tend to miss “whisper” numbers on the Street (sometimes their very good management is actually the problem, as the Street gets too optimistic about management’s ability to deliver). I think this could happen in either the 4th quarter of this year or the 1st quarter of 2007.

It is also true that if revenue grows faster than I project, particularly in 2007 and 2008, the stock’s value should be higher. If operating margins were to increase, the company should also have higher intrinsic valuation. I don’t expect higher revenues (see reason three below) and I also don’t see higher operating margins (see reason four). It is also worth noting that there can be no assurance that the company’s products will remain fashionable for the next ten years, so future revenue growth could be negative, which would have a significant negative impact on the shares. Is the risk worth it?

Reason 2: Me

A successful investor has to control his own emotions. He also needs to know the limits of his competence – his circle of knowledge where he can make decisions better than others. In my case, TRLG does not fit that profile. This stock is really outside of my area of expertise. I purchased the stock not because I saw great visions for True Religion (though the company’s management does). I purchased the stock because I loved the growth rate and the balance sheet (check out the balance sheet on Yahoo or at your broker’s research site. It is as pristine as can be, with more cash than liabilities).

Back in early 2006, about 75 days after I purchased my shares, the stock hit an all-time high of $24.61. I decided not to sell, because I let the market convince me that I should trust my most aggressive estimates that showed an intrinsic value of $27-$30 a share. I was the fool in this case, since the stock then took a major dive, back down to $15. Had I sold, I could have bought back in when the stock hit that price point, which was a significant discount to my low-range value of $17 per share. I don’t want to make the same mistake again.

For what it’s worth, my lack of special knowledge means that I may be underestimating the company’s prospects. But I would rather underestimate them than overestimate them.

Macro Trends

While I lack special knowledge of fashion brands, I can see how macroeconomic factors will likely impact retail – negatively. The economy, while still strong, continues to slow. With a stabilization, or even decline of home prices, and the imminent retirement of spendthrift boomers, we face a high probability of declining consumer spending, which should put the entire category at risk. While the high-end of any market usually holds up best in a downturn (wealthy folks have wide, deep income streams), strong growth rates mean acquiring new, “mass affluent” customers. Faced with the need to save more, these folks are less likely to splurge on $300 jeans, so I expect that more aggressive growth rates that would further lift intrinsic value (and ultimately share price) are less probable than the rates reflected in my DCF analysis.

Company specific issues

Apart from the foregoing, TRLG has some other company-specific risks. The stock is controlled by a single shareholder, who also happens to be the CEO. In fact, insiders control a significant amount of the stock, and therefore not only have control of management, they also control the board. While this is not necessarily a problem, after all, some of the best run companies in the world are controlled by single shareholders, it is even more important than with other companies to see if management is acting in the interests of all shareholders.

While management appears to be running the business well, they are taking steps that are not nearly as shareholder friendly. While they have stopped issuing options (the remainder of which will eventually be exercised, rest assured), they are instead issuing large amounts of restricted stock. Thus, as shareholders, we are seeing our slice of the pie get smaller. The pie is getting bigger at a very fast pace, so the size of our slice is getting larger, but it is doing so by getting thinner and longer. I like to look for companies that are net-repurchasers of stock. That is, the repurchase more than they issue (including options). That way, I know that my slices are getting wider as well as longer.

True Religion is not doing so. They are not repurchasing stock, nor are they issuing even a small dividend. While this is not uncommon among small fast-growing companies, TRLG has demonstrated that it doesn’t need additional assets to fund its growth. No where has TRLG indicated that it has definite capital plans that might require the cash to be reinvested in the business. So why not return cash to shareholders?

Likewise, why pay employees with stock? Why not pay them cash bonuses (from current year revenues). This will reduce the cash-hoard slightly, but again, the cash doesn’t seem to be required. Employees can purchase the stock in the open market if they consider it such a value.

Finally, when management controls a company like this one and cash starts piling up, management gets all sorts of ideas about various projects that would be interesting to undertake. Usually these ventures produce far lower returns than the business itself, and ultimately destroy value. With no real checks to prevent this, as a shareholder I must be concerned about the uses to which the cash will be put.

Market environment

TLRG has been a favorite stock of the shorts. As of August 10, it had nearly 40% of the float sold short. This, ironically, is often a bullish signal. Since the short shares have to be bought back, large short positions guarantee future purchase volume (though not higher prices). However, as the stock has been rallying in the last few weeks, various shorts have undoubtedly been closing their short positions by repurchasing the shares, potentially at a loss, as the stock market has rallied, rather than faltered, during this unusual third quarter.

Once that short-covering purchase demand dries up, however, we are likely to see a downward drift in the price. Some shorts, convinced that technical factors will drive the stock down to the mid-teens again, will start selling short again. Such a reversal is likely to see us head lower.

The bullish case

The bulls can argue that revenue growth will remain strong (the third quarter is the biggest, revenue wise for the company. If we see continued strong growth in the

However, the bullish case also relies on continued short squeezing, and potentially on a sale of the company. I believe that, at current valuation, no such sale is likely. An acquirer would get some cash, the trademarks, and a heap of goodwill. And that is BEFORE paying a takeover premium. Similarly, an effort to take the company private, which is possible because insiders could commit their stock, would still require significant amounts of debt, at least $300 million worth, which the company could probably pay, but would significantly impair net revenues, as the interest payments would be on a scale comparable to operating earnings.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

What's your Sloth Story

We'll take stories slothful waste as well.

Mine actually involves using a full service broker. My parents are successful people, but not what you would call successful investors. They are employees who have saved diligently and profited from the long bull market.

Anyway, when I was 12 (and definately no investor), I decided I wanted to purchase stocks. So my dad took me to Merrill Lynch (which a savvier investor would not have done) and helped me open an account. At the time Merrill was offering a program that enabled you to purchase based on dollar increments and not round lots (which I could not afford). I decided to invest in the bluest of blue chips. T. Yes, American Telephone & Telegraph. I purchased 7 plus shares with about $200.

I was excited about the dividend and the strength of the company. After 12 years I had shares in Lucent, AT&T, NCR, Comcast, Avaya, Agere and other companies. I think my position was worth nearly $1000, which wasn't bad. But I had never really collected any dividends because of the account fees. When the telecom market collapsed, I wound up with an account balance not significantly different from my initial investment and I still had fees I owed.

I sure had been slothful, but I had missed the boat.

The Slothful Investor

Before I continue, however, I would like to give a shout to the Oracle of Omaha, who finally married his long-term girlfriend. For those who do not know, the Buffetts separated in 1977, but incredibly never divorced. Susan Thomson Buffett, Warren's late wife, remained on the board of Berkshire, and by not going through divorce proceedings enabled him to keep control of Berkshire. With her death in 2004, however, the Oracle has changed his plans for his fortune and has decided to finally tie the knot with Astrid Menks.

Back to the issue of sloth, however. Slothful investing is the natural correlary of focus investing. Since your few best ideas are going to be much better than your other ideas, you spend alot of time just sitting on your existing positions and looking for something better. Only occasionally will you find it. Isn't this a major reason why trading is so much work? Following the market obsessively takes huge amounts of time. Worse, much like executive focus on meeting the quarterly numbers, it takes your focus off of what really counts - the intrinsic value of the businesses. Much, much worse, it tends to generate fees. Lots and lots of fees.

Buffett as a Slothful Investor

The best example of sloth I know is Buffett's purchase of the Washington Post in the early 1970s. This stock gets far less play than his investments in Coca-Cola, Geico, or even L3 Communications (a position that has since been liquidated). To understand this purchase, zou have to appreciate the publishing business and Buffett's timing.

Unlike most public companies, nearly all media outfits are controlled by a family or major shareholder. This is true regardless of the medium, everything from television (CBS, Fox) to to newsprint (NYT, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, USAToday). Most newpaper companies operate with multiple classes of stock. This is the result of the fact that most of these companies were originally closely held family businesses. When they went public, the family wanted to make sure that it could maintain editorial control. Unusually for companies with multiple classes of stock, this has probably benefitted shareholders. News outlets obviously have editorial slants and their readers are often motivated to purchase that content based on their own views. A sudden change of control, and concomitant change of editorial direction could have readers scrambling for the exits. (Can you imagine the shrill cries of Daily Kos if the NYT were acquired by Rupert Murdoch?) So protecting the editorial direction is part of protecting the franchise.

But back to 1973. Buffett valued the company at $400 million. In one of his annual reports, he notes that anyone he asked felt the company was worth $400 million. Mr. Market was asleep that day, because it was valued at $80 million. Buffett purchased $11 million in a tender offer, which gave him a 15% share of the Class B stock.

He wanted to purchase more, but Katherine Graham, the publisher who had IPOed the paper after the death of her husband and ran it for years, was influenced by her son who felt that no one but the Graham family should have a larger share. Sticking with his strategy of investing only with management he likes, he complied with their request. (I actually had the tremendous pleasure of sharing a limo with Mrs. Graham on two occasions. She received the Benton Medal from the University of Chicago, my alma mater, and I was working in the office of special events. I picked her up at the airport and took her to the president's house. When she departed, I shared breakfast with Mrs. Graham, the University president and his wife, and then rode in the limo back with her. She was quite a conversationalist and down to earth.)

Today, his 1.7 million share position is worth $1.4 Billion ! The stock also continues to pay a solid dividend. At $7.80 per share, the annual dividend that Buffett collects exceeds his initial investment, and he has been able to use it to invest in other projects over the years. This one investment counts for the bulk of the tremendous outperformance of Berkshire since 1965. He has never sold shares in the company. Essentially, he has been able to sit on the position and experience rising dividends.

Life as a Slothful Investor

The best thing about slothful investing is that it enables you to live your life. Once your investments are on autopilot, you can focus on the things that are really important to you, like travel, or education, or your family.

In my case, I made very few moves last year. My three big changes were to liquidate a position in a small cap mutal fund. I sold FBRVX and kept PRCGX. While this hasn't been a horrible decision, it turns out I would have been better off with the FBR fund (I orginally purchase in 2001 and had made no move since). I sold it becuase I wanted to reduce my exposure to small cap funds.

Instead, I decided to make a "major purchase" of 200 shares of BAC. I will cover this in more detail in another post, but basically I purchased it because the stock was cheap, large cap financials were unloved, I expected a rally after the Fed stopped raising rates, and I was going to be paid handsomely to wait. I purchased in the mid 40s and one year later we are around $51, but I have also collected the dividends.

Finally I made a purchase in November that turns out to be my one position where trading would really have helped. TRLG is one of my favorite companies. Since we are now $10 above where I purchased last November, I need to reevaluate this stock, but had I traded, I could have sold at $24 only weeks after purchasing at $13. I could then have repurchased the stock at $15 and rode it all again to $22 where we are now. But the truth is, I am not looking to call tops or bottoms. I am simply looking to purchase dollars on the cheap.

I have not made a trade in nearly a year. Still, I am up over 20% since this time last year. My limited work on this has enabled me to refocus on my quadrant "e" work, apply and get accepted to business school, sail and still find a little time to remind my girlfriend why she is so important to me. (Ok, I could do better on this last point).