Unfortunately there was a problem with Blogger photos, so it didn't embed.

So, I will try again.

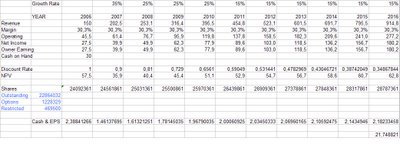

The model covers a ten year valuation of the company. Basically, what I have done is take the actual net cash and equivalents as of December 31, 2005, and the actual number of shares outstanding, plus the number of options outstanding, plus the number of restricted stock shares issued, and project the following: annual revenue growth, operating margins, tax rate, net income and owner earnings (net income plus depreciation less capital expenditures), and future equity dilution.

Starting with 2006, I project revenues of $150 million. This represents a 50% increase over last year's $102 million, and is roughly the amount that management projects. Going forward, I expect slower growth. It is possible that my growth rates are too conservative, but how mainstream can $300 jeans be? International sales are also flagging, though management has insisted that this will improve shortly. Management insists that it can turn the brand into a $1 billion per year business, though how long is not clear.

Next up is margins - a measure of how profitable those revenues are. The company appears to be consistently running an operating margin of 30.3%. It is important to distinguish between gross margins and operating margins. Gross margins is the spread between the sale price and the cost of the product sold, expressed as a percentage of the sale price. Thus, if sell for $300 a pair of jeans that cost you $150 to produce or purchase, your gross margin is 50%. However, there are still the other operating expenses, like employee, marketing, legal, and others, to pay. These are generally lumped together under Selling, General and Administrative expense. After you pay those expenses you arive at operating margins. That is, your profit as a percentage of sales after you have paid all operating expenses.

(Please note that the spreadsheet is in a German version of MS Excel, so don't be thrown by the commas. Germans use commas where US uses decimal points, and vice versa. Funny, isn't it? But I digress).

TRLG has benefitted from higher margins in recent months, expanding to about 52-53%. Most of this margin expansion is coming from the impact of retail stores, which enables the company to capture the additional gross profit between wholesale and retail. Unfortunately, it also means the company has proportionately higher selling, general and administrative expense, because there are rent, employees, utilities and other expenses to pay in operating that retail store, so operating margins are remaing about the same as before the retail stores. (The amount of revenue is higher, because revenue is now happening at retail, and not only at wholesale prices, so that margin is being earned on a higher top line number).

From there one has to consider interest expense (none, since the company has no debt, and appears to require no major investment to grow revenues, since all products are produced by contract manufacturers). This leads us to taxes. I assume a tax rate of 35% for all years. Here, I am simply projecting the current maximum corporate tax rate into the future. This is actually one area where I have not been conservative. It is likely that the US government will raise taxes, particularly on corporations, in the next 10 years, in order to combat rising deficits.

After the taxes are paid, we have Net Income. To this we need to add depreciation (a non-cash expense), and subtract capital expeditures. In mature businesses, these numbers are often very similar, as the business tends to need relatively little capital. What makes TRLG interesting is that it has virtually no cap-ex at all. In fact, it has virtually no long term capital commitments, other than some leasehold improvements at its corporate offices and retail stores.

So, Net Income and Owner Earnings are essentially the same.

The Discount Rate

One of the most crucial numbers you can chose in investing is an appropriate discount rate. The discount rate is used to reflect the time-value of money. Obviously, if I offered you $1 today or $1 in ten years, you would rather have the $1 today. I have to "discount" the value of the dollar in ten years to reflect the risks that you assume in waiting so long to get your money.

The first time they hear this, most people think of inflation, and in fact the idea is very similar. But where inflation measures the discount that would be required to maintain purchasing power, investors need to use a different number. We have to ask ourselves, what is the opportunity cost of the capital? Since if we didn't put our capital into this investment we could put it into a different one, we should really use a number that reflects what would happen if we were to earn the market return. I estimate this at about 10% (though in my first post I mentioned that the compounded rate of return of US stocks since 1926 is actually 9% - and that was in 1999 at the height of the bubble).

Once I have discounted those earnings into the future, I then need to divide the discounted earnings by the anticipated number of shares outstanding, so see how much earning power one share should have.

Thus far this year, management has cut out issuing itself options. Instead, it issues itself restricted stock. This year, the company issued employees 450,000 shares of restricted stock (it also issued some as settlement to outsiders). I see no reason to expect that management will become more frugal going forward, so I estimate the increase in shares outstanding by 469,000 per year. I then divide each year's discounted earnings by the anticipated shares outstanding.

All that is left to do is sum up the values. This produces a Net Present Value (reflecting the sum of all the present values) of the future cash flows of the company. Those cash flows are worth about $22.

Unlike most DCF models, I am assuming no residual value beyond the measurement period (generally, investments in stocks are considered to have infinite valuation periods, and you have to do that special calculation. In the case of this stock, where the true long term sustainability of the business is really a question it makes no sense to assume an infinite valuation period. The extra margin of safety is key).

No comments:

Post a Comment